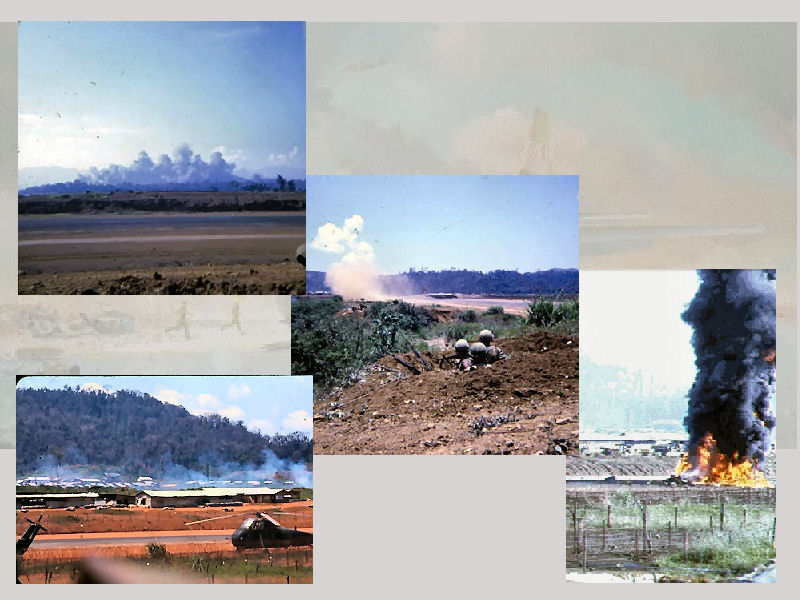

Some of us Won't Ever Forget May 1968 at Kham Duc

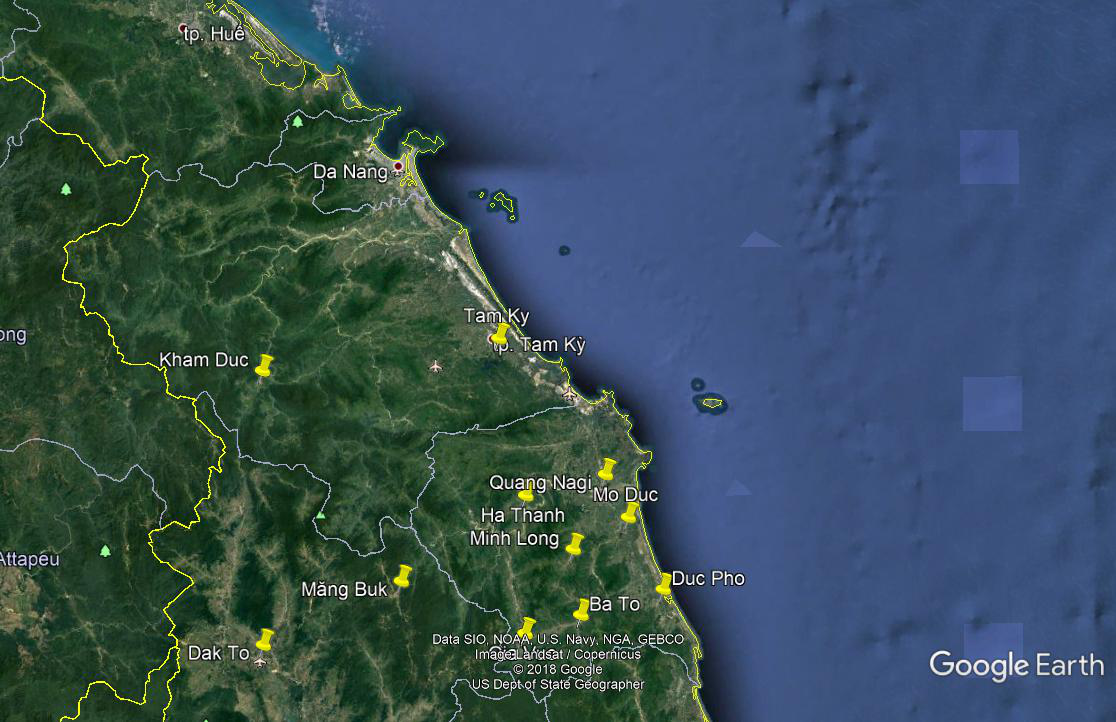

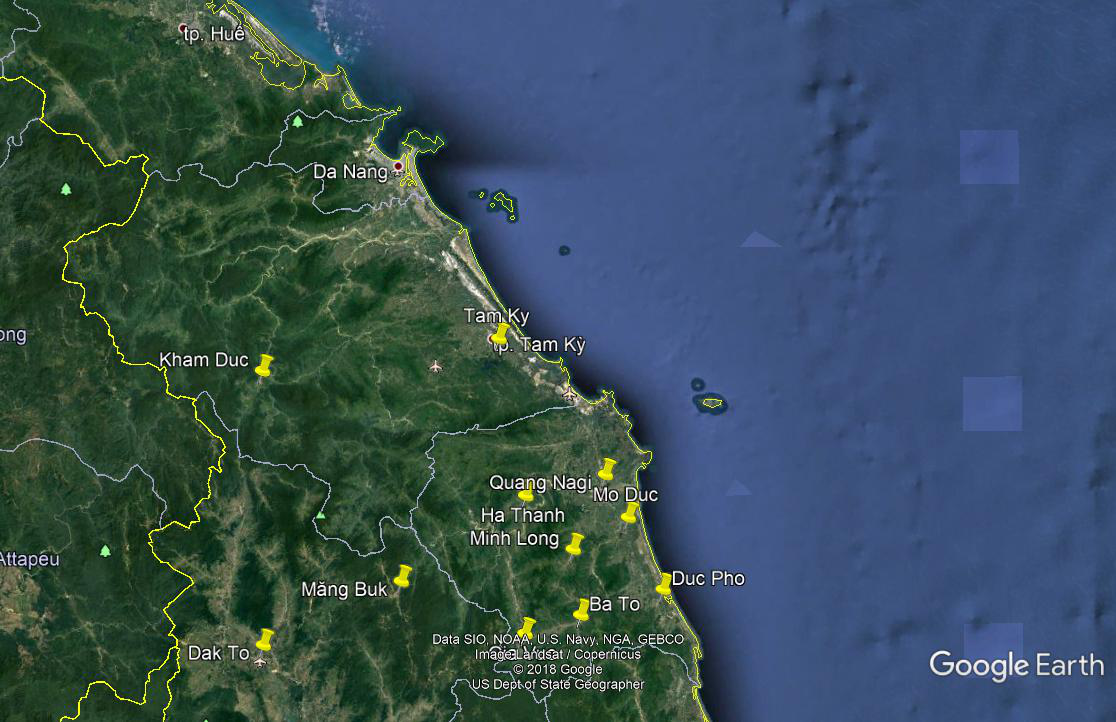

In the 1950s Kham

Duc had been a destination of South Vietnamese President Ngo

Dinh Diem, who liked to hunt tiger and other big game in the

surrounding jungle-covered hills. Diem had a 4,800-foot airstrip

constructed there in the mid-1950s for his presidential aircraft

along with his private hunting lodge. Wooded hills rose on all

sides. It was situated south of Khe Sanh in the northern section

of Quang Tin province, about 75 miles west of Tam Ky and only 10

miles from Laos . Kham Duc sat beside national highway 14, which

paralleled the Laotian border and had served as an avenue for

insurgents to move from Laos north and east to the coastal plain

around Da Nang. The camp was dominated by  steeply

rising terrain in all directions. The hills were densely

forested with double and triple jungle canopy. It was obvious to

those on the ground at Kham Duc and to the aircrews who flew

into the airfield that the camp was vulnerable to an enemy in

the surrounding high ground.

steeply

rising terrain in all directions. The hills were densely

forested with double and triple jungle canopy. It was obvious to

those on the ground at Kham Duc and to the aircrews who flew

into the airfield that the camp was vulnerable to an enemy in

the surrounding high ground.

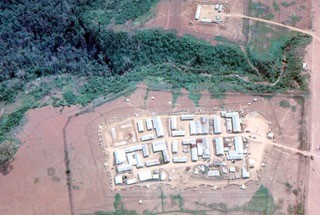

For years, the camp at Kham Duc had served as a base for

intelligence gathering operations along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

By early May of 1968 allied intelligence sources realized that a

large number of North Vietnamese were gathering in the mountains

around the camp.

..................................Jake 73 tells us...........

" Gentlemen: In 1968, the Jake FACs of Tam

Ky supported the 2nd ARVN Division in Quang Tin

Province in Southern I Corps. Most of our activity was focused

in the central and eastern lowland areas of the province –

coincident with (but certainly not coordinated with) that of

the 23rd Infantry (Americal) Division headquartered

over on the coast at Chu Lai. At the far western end of the

province was the Special Forces camp at Kham Duc. I was

in the camp quite a few times before I was made aware of the

several missions that took place there. (One of my many

trips there was to deliver badly-needed groceries I had

scrounged for them due to the poor support by their C team.)

While the overt function of the

SF mission there was to serve as a basic training site for

CIDG recruits, an ancillary (and well-hidden) function was

to serve as a launch site for SOG team missions over the

fence.. My discovery of that fact and later participation in

support of those missions is detailed in “Prelude To A Medal

of Honor” in Vol I of Cleared Hot.

In the period leading up to

the attack, the Jakes had closely watched, reported on, and

photographed the construction (mostly at night) and progress

of a brand new southbound road which paralleled Rt. 14, just

over the province border. We repeatedly noted and complained

to I DASC that this was a major effort as the road

construction was progressing at about a klick per day –

impressive, given the terrain. We felt that our intel was

important, but that it was being either ignored or disregarded

at DaNang. It was our thought that the road would either turn

eastward to facilitate an attack on Da Nang or Chu Lai or

continue south toward Pleiku or some other II Corps objective.

The silence from I DASC was deafening.

On the night of May 9th,

the camp was attacked with mortars and rockets, a prelude to

an attack by a force of some three to fou r

thousand North Vietnamese Army troops of the NVA 2nd

Division. (Said to have been “lost” to US intel following

their defeat at DaNang at the Tet offensive.) The decision was

made to reinforce the camp. This was not a local decision, but

involved not only the Americal Division commander, MG Samuel

Koster; LTG Robert Cushman, CG of I Corps forces; Col.

Johathan Ladd, CO of the 5th SF Group; but also

General William Westmoreland, COMUS-MACV. Evidently the Jake

reporting got more visibility than we were aware of.

r

thousand North Vietnamese Army troops of the NVA 2nd

Division. (Said to have been “lost” to US intel following

their defeat at DaNang at the Tet offensive.) The decision was

made to reinforce the camp. This was not a local decision, but

involved not only the Americal Division commander, MG Samuel

Koster; LTG Robert Cushman, CG of I Corps forces; Col.

Johathan Ladd, CO of the 5th SF Group; but also

General William Westmoreland, COMUS-MACV. Evidently the Jake

reporting got more visibility than we were aware of.

The Americal Division

reinforced the camp but hours later was ordered to withdraw.

The attack of the camp and the (not much) later withdrawal was supported by a major air support

effort which took priority over almost all other RVN air

operations. The fighter pilots, airlifters, helo pilots (and

especially the Jake and Helix FACs) involved will well remember their participation. The on-the-ground

activities of Helix FAC Skip Smothermon and this Jake FAC writer in the camp are etched in our memories. A number of KD stories by

more than a few FACs are detailed in the several volumes of

Cleared Hot.

The Kham Duc dustup created a

multitude of vignettes which detail individual effort, bravery

and heroism on the part of many souls, some of which remain

there. Among these stories are the pre-KD operations and

subsequent withdrawal from the NVA attack of the KD outpost at

Ngok Tavak, the CCT Colonel who (quite mistakenly) sent three

brave folks back into a deserted KD in an otherwise empty

(except for the crew and me) C-130, Lt. Col. Joe Jackson’s

rescue of the three combat controllers from the deserted camp,

the three Americal soldiers who survived an attack of their OP

and who were later rescued, the rescue of an A-1 pilot who was

forced to eject altogether too close to the camp, and many

others.

An excellent account of the

Kham Duc story was recently published by James D. McLeroy and

Gregory W. Sanders who state that Kham Duc is “One of the

least known and most misunderstood battles . . .” Their book

is “BAIT; The Battle of Kham Duc Special Forces Camp.” Both

authors are Army officers, both hold master’s degrees in

history, and both were personally involved in the

battle. McLeroy was OIC of the SOG launch site at Kham

Duc and Sanders served as an infantry officer and psyop/civil

affairs officer with the Americal Division.

Their book is exhaustively researched, well written and quite accurate. There are extensive footnotes. an analysis section, and an exhaustive index. There might be minor inaccuracies, but the only part I found to be less than properly detailed was their accounting of how the combat control team got sent back into the camp.

That’s because they weren’t there; I was."

(In a recent email............ from Jake 73 (Chuck Johnson)

"I had been at Da

Nang for an engine change or something, and on return to

Tam Ky was advised that the ALO, one Mel Sleeth, had gone

to Kham Duc and I had orders to relieve him ASAP. I took

the time to pack a B-4 bag, complete with my Nikon, clean

underwear, and a couple of novels as I knew things could

be rather quiet out there. When I landed, Sleeth ran to

the airplane and told me to NOT shut down, as "I had it"

and he was "outtahere". He got in without a further word,

took off, and I was left standing there with my B-4

in one hand, the Nikon in the other and wondering

just what I had got myself into. Little did I

know.

Somewhere - Lord knows where - are the photos I shot while on the ground at Kham Duc. I was in there when Skip lost part of his wing and ruddered his very sick beast onto the runway. What he doesn't often tell is about the EM that went out to greet him and bring him back to the bunker. As I recall, he said, "I'll bet that guy is thirsty" and took the time to grab a cold beer to take to him. We had a lot of cold beer, but none of us had the time to drink it just then as we were otherwise occupied trying to not get overrun. "

Skip Smothermon, Helix 41 ("This is how it was")

"Mayday, Mayday, I’ve been hit!"

Those were the first words out of my mouth just milliseconds after the biggest "BANG" I’d ever heard. The mission had started normally enough. The Army Special Forces camp of Kham Duc, near the Laotian border, had been under fire for a couple of days and the decision had been made to evacuate all personnel. The weather, initially poor with fog, had improved and airlift and fighter air had been laid on for one of the largest troop moves in the war. A battalion-sized unit of Americal Division troops had augmented the regular Special Forces unit. They were opposed by 4,000 to 5,000 NVA and were under heavy mortar, rocket, and automatic weapons fire. I had been at the Tactical Operations Control duty desk most of the night. As soon as I was relieved, I requested to join the effort as a FAC.

When I arrived over the camp there were two or three sets of fighters working both sides and the east end of the runway. Airlift C-130s and C-123s had started landing, stopped due to weather, and started again. After becoming familiar with the situation, I began working to find the .50-caliber gun position that had shot down one or two aircraft, including a loaded C-130. I was still working on that gun with my third or fourth set of fighters, and had just rolled in for another marking pass, when the world's loudest "BANG" sounded near my right wingtip. The O-2 suddenly entered a steep, rolling turn to the right. One look at the wing provided me with images of metal fragments hanging where three to four feet of wing used to be. My voice rose to a high pitch with those dreaded words - "Mayday, Mayday, I’ve been hit. I’m going down"

The aileron controls were severed, and twisting that silly

control wheel to the left was no help. Fortunately, my left

foot was pushing the left rudder pedal through the firewall

and bit-by-bit the turn slowed. After a quick assessment of

aircraft capabilities, I determined that the elevators were

okay and that I could almost maintain straight ahead flight,

but was losing about 400 feet of altitude per minute.

Somewhere during this time the radios went out (constant

turning of the flight control wheel tends to twist and break

radio cords), so I had no way to tell anyone that I was

attempting a landing at Kham Duc. Several right turns brought

me to the west end of the runway, and only a little bit high.

I lined up on the strip only to find my windshield filled with

a C-123 going the other way! The next dodging right turn was a

lot faster.

When I came around again the lineup was less than perfect, but the landing was great! I had a runway under the wheels! After skidding and rolling down the runway for a bit; the thought occurred to me that my now non-flying machine was a detriment to evacuations while on the runway, so I promptly steered off into the adjacent dirt shoulder. After shutting down, a very shell-shocked FAC climbed out of the aircraft to find a jeep skidding to a stop by the right wing. "Get in," said Special Forces Sergeant Walker. Get in I did, as the camp was under heavy mortar and small arms fire. We sped back to the bunker area and dove (as in did not saunter) into the nearest bunker. I found people on radios, field phones, etc, everywhere. After a short period of time I asked Sergeant Walker, who was still hovering near me, where the nearest radio might be so that I could talk to the Air Force folks. He asked me to follow him and we ran to the next bunker, which turned out to have been recently abandoned by the Airlift Combat Control Team.

In the bunker, I found an HF set already tuned to the I-DASC frequency. After proving to the folks on the other end that I was alive and mostly well, and closing out my flight plan, I was told, "Stand by." Shortly afterwards the DASC called back informing me that I was now the Ground ALO. Imagine , I (thought that) I was the only Air Force guy on the ground. Further instructions followed: "General Momyer directs you to report to the Army commander and provide any support possible. Also, you are to remain at Kham Duc until the last evacuation flight." Joy and gratitude washed over me as I reminded the DASC that I had not volunteered to be in this high level position.

For

the next four hours, due to the complex nature of the tense

situation, I found it necessary to expose myself to some of

the hostile fire in order to talk on the FM radio. I snuck in

and out of the bunker, and sometime during this period the

environment turned more hostile. I had climbed to the top of

the steps leading out of the bunker, when a mortar round went

off just outside (one small piece stung my face and reduced my

hearing for a bit). That was the last time I went to the top

of the bunker steps. Shortly afterwards, it got really warm!

Napalm impacting on a nearby barbed wire perimeter tended to

produce heat. That heat was welcome!

For

the next four hours, due to the complex nature of the tense

situation, I found it necessary to expose myself to some of

the hostile fire in order to talk on the FM radio. I snuck in

and out of the bunker, and sometime during this period the

environment turned more hostile. I had climbed to the top of

the steps leading out of the bunker, when a mortar round went

off just outside (one small piece stung my face and reduced my

hearing for a bit). That was the last time I went to the top

of the bunker steps. Shortly afterwards, it got really warm!

Napalm impacting on a nearby barbed wire perimeter tended to

produce heat. That heat was welcome!

During the remaining time, I briefed the ground commanders on their responsibilities during the evacuation, coordinating through the I-DASC. This allowed the evacuation to proceed in an orderly flow with minimum time on the ground for the aircraft. My efforts included directing such things as the best spot to position troops to get on the evacuation aircraft and time remaining before the next arrival.

Finally, someone ducked into the radio bunker and yelled, "Lets go, Sir!" I did just that, and ran out to the prescribed spot abeam the runway. A C-130 soon came by doing a quick turnaround on the runway, and I climbed aboard nearly the last flight out of Kham Duc , along with about 150 Special Forces troops and their C-I-D-G (Montagnard) contingent. We did a lot of praying that the aircraft would remain flying through the continuous small arms and anti-aircraft fire. After a bit it became obvious that we were free and clear and everyone breathed a collective sigh of relief.

The flight to Danang was short. All sorts of welcoming troops met us, including 20th TASS folks who took me by the TASS headquarters to drop off my gear. Then they delivered Chuck Johnson and me, a pair of weary FACs, to the office of U.S.M.C. General Cushman who gave us a drink (only one each) and proceeded to quiz us on the recent events. Afterwards, we were returned to the 20th TASS and flown back to Chu Lai. At some point during that evening’s inevitable trip to the officer’s club, I met one of the pilots of the last set of fighters I'd worked that morning. He enlightened me as to the source of the "BANG!" He was in position to roll in when he observed the black explosion around my right wing tip. "Probably a 37mm round from the way it looked," he said. Thus, the last mystery was answered and my day was ended.

In another email, Jake 73 says..........

"................... by the afternoon of May 12, the majority of the personnel had been airlifted out of the Kham Duc SF camp. The Air Force personnel (the crew of C-130 #55-013, the CCT crew and me) had gathered together just outside the TOC. We were advised that the camp was about to be overrun and that the Army was forming an “E&E” party to escape through the jungle. Lt. Col. Daryl Cole and his crew were there as their C-130 had taken ground fire on landing, resulting in a fuel leak and a shredded tire. They considered it non airworthy – but on hearing the part about E&Eing through the jungle, reconsidered that decision. (Listen for a moment as Jake73 tells us "How it was")

Cole and his crew inspected their bird and Cole announced that if the cargo could be offloaded and the shredded tire removed, he and all other AF folks were leaving – provided he could get it off the ground. As for Freedman, Lundy, & (third guy), we left on a C-130 that had been damaged - and to be truthful, none of us (including, I believe, the crew) knew for sure that it would fly. We had to cut away a shot-up tire which was really quite a chore and took forever, especially with the stray VC mortar landing on our side of the ramp. We then had to move crates of mortar and other ammo that had spilled out of someone's cargo bay on landing in order to get onto the runway and hope it didn't catch fire from the fuel that was leaking from the wing tank. Tough work, but when one is as motivated as we were there is a lot of energy to be summonded. Take my word for it, it was not a fun job, especially with incoming mortars. But I digress. The ironic part was that onboard was a spare tire, but with no jacks or other equipment it was just dead weight. We rolled it off and aside.

We boarded the aircraft and it actually took off with but a single right main tire and a 4,000 lb fuel imbalance which resulted in a pronounced list. In response to several fervent prayers, that bird flew after taking off on three engines – the No. 1 engine being started only after getting airborne due to the hazard of fire from the (continued) fuel leak on the left wing. The fun continued when mortar rounds impacted nearby about at the point of rotation, impacting the nose and shattering two of the pilot’s side windows. Kham Duc grew smaller as we headed for Cam Rahn Bay, looking forward to landing on a foamed runway. I had been in the command bunker when the crew of that bird decided to try to make a break for it. They wouldn't take a load of grunts as they weren't sure we could safely get it off the ground or make it stay in the air, but they announced loudly that they were leaving and any air force folks that wanted to could join them. Being flat scared, I took them up on the offer, along with the three CCT guys. We landed on foam at Cam Ranh Bay, and I followed the CCT guys out the hatch when we came to a stop on the runway. The landing was exceptional – quite smooth, with touchdown perzakly where Cole wanted it. We came to a halt and our intrepid controllers exited out the side door followed by yours truly. I bumped into one of the CCT folks as all three were standing at rigid attention while an irate O-6 who knew nothing of things back in the camp provided a rectal reaming, accusing them of not doing their job and directing them to an adjacent C-130 which was cranking. I had the nerve to ask about how to get to Da Nang and was told to go with them as the bird was going to recover there. Not thinking exactly straight at that point, I went.

Long story short, we landed at KD – transportation provided by Major Jay Van Cleef, 1/Lt Rollin Broughton, a nav whose name escapes me and their loadmaster, T/Sgt Green. Van Cleef screeched the Herky Bird to a halt, Major Gallagher & Co. leaped out the side door and Green & I lowered the ramp to assist the remaining Amy personnel aboard as Van Cleef did a 180 to ready for takeoff-- nothing in sight but gomers and a guy with a .50 shooting up the Herky Bird. It was enough to make one's little heart go pitty-pat. We took off with the ramp not yet closed, and the CCT trio lying in the ditch just off the runway. Not a good day for them. The only problem with that was that the camp was empty. Not a soul was in sight and we were getting hosed by a number of the camp’s recent visitors. Green screamed something to the AC on the intercom and we hurriedly left. I’m not sure the ramp was fully closed until well after we were airborne. I was glad I found something to hang on to.

When we left the camp (there were) three GIs were left behind. Sergeant Edward (Ron) Sassenberger, Specialist Wilbert Foreman, and Specialist John C. Colonna (E Company, 2/1 Infantry, 196th Infantry Brigade of the Americal Division), were assigned to OP 2. This was one of the six OPs attacked and overrun by the NVA 2nd Division that day. In the case of OP2, an initial barrage of 60mm mortar fire was followed by a platoon-sized assault force that threw hand grenades and rushed the bunker, firing automatic weapons through the bunker ports immediately after impact of the last mortar round. All three were at the far end of the bunker, shielded from the grenades by the bodies of their comrades. They received serious injuries, but survived.

After the NVA moved on, they left the bunker, rolling and falling down a very steep slope into a deep gully. The three had no web gear, no steel pots, no flak jackets, and no radio. They did have two M-16s and a pouch with 13 magazines. Foreman had been wounded in the hand by a grenade and Colonna had a leg wound that prevented him from walking without the support of the others. They decided to E&E, but soon encountered two enemy soldiers. Sassenberger killed both. They were pursued, but after traveling some 300 meters, artillery rounds impacted in the area and the enemy stopped chasing them.

At dawn on the 12th, the

three observed a Medevac helicopter hovering in the area.

They waved and thought they had been detecte d,

but the helo left as a result of intense enemy small arms

fire, coupled with friendly artillery fire. A B-52 strike

followed, and then the three moved approximately one klick

away. They had seen a CH-47 burning on the runway, and their

first impulse was to return to Kham Duc. But they concluded

that that was not possible due to the air strikes around the

camp.

d,

but the helo left as a result of intense enemy small arms

fire, coupled with friendly artillery fire. A B-52 strike

followed, and then the three moved approximately one klick

away. They had seen a CH-47 burning on the runway, and their

first impulse was to return to Kham Duc. But they concluded

that that was not possible due to the air strikes around the

camp.

That night they slept under a tree in heavy brush near a stream, and on the morning of the 13th they observed a B-52 strike on OP2. They felt they were unable to reach the camp, so they decided to attempt to return to their division HQ at Chu Lai, however this was almost 100 miles away. They moved to the northeast, but were spotted by FACs several times. Each time the FAC marked their position with a smoke rocket, but they successfully avoided both strafe and napalm from several sets of fighters. That night they observed a fire at an NVA camp, and many personnel.

On the morning of 14 May they succumbed to both hunger and fatigue and decided to return to the airstrip, hoping to find rations. Approaching the camp, they spotted a figure walking through the SF compound, but could not tell if he was friendly or enemy. They remained hidden and decided to try to signal a FAC and take their chances with another air strike.

Just prior to coming to Kham Duc, Foreman had received a large batch of long-overdue mail and had a pocket crammed full of it. They chose the largest bomb crater and formed a five-foot S-O-S using the letters and envelopes. Several FACs overflew their signal without spotting it. They did not reach the airfield that day, and spent the night in a hastily constructed grass lean-to without incident.

On the morning of 14 May I was back over Kham Duc, carefully watching above for further B-52 strikes and working hard at destroying the rest of the munitions on the Kham Duc ramp. In a quiet moment between flights, an Army OV-1 Mohawk cruised through the area and we discussed the destruction below. We speculated about a rather odd-looking bomb crater and I went down to take a look at it. What we had spotted turned out to be Foreman’s three little white letters. The Mohawk photographed it and left. I completed my sortie and returned to Chu Lai, noting the sighting and the coordinates in my intel debrief.

I later learned that my sighting and report of the SOS and the Mohawk crew’s photos resulted in a rescue mission that brought all three personnel out. I got to visit them while they were being treated in the Danang hospital. They had endured the B-52 strike and several fighter strikes, and survived to tell the tale. Reports vary, but one indicates that at least one of the three was also wounded by friendly fire. All had burst eardrums, but they were alive. It was an emotional meeting and, despite the air strikes, the FAC force won three new fans that week. Every May 15th I remember those guys, and as they got rescued on Mother's Day I think of them once a year. What's interesting is that of the three, only one would talk to me about it when I contacted them a couple of years ago."